User stories are a valued component of agile or scrum development. In project management, user stories helps keep teams focused on the end goal of “why” a feature is needed. It also helps to provide a deeper context for everyone working on sub-items related to a larger feature. Writing user stories for agile or scrum is easy. In this post we wanted to give you some examples and guidance on how to write better user stories.

Why Write User Stories?

Precise and simple communication

Simply listing a set of tasks for your team, while sometimes effective, can be confusing. This can stem from a number of causes: vague context, unclear expectations, and being overly technical.

Task: Implement Sprintly GitHub Integration

User Story: As a user, I want Sprintly to integrate with GitHub so that I can view GitHub activity related to a Sprintly item, in the item’s activity feed.

The user story makes it clear that the integration needs to result in GitHub activity being tracked in Sprintly. In comparison, the task merely suggests that integration is needed, but it’s not clear how a user would benefit from it.

For large requirements documents or use cases, it’s easy for the value and focus to get lost. User stories are the perfect middle ground between large, overly detailed documents and vague tasks.

Software development teams are always on a time-crunch. User stories are easy to understand, relatively easy to write, and easy to maintain. A user story is written in plain English, which avoids confusion with unfamiliar terminology or jargon. During time sensitive projects, quickly pushing out several user stories works great at providing your team with an overall understanding of the project. Details and sub-items can be added as needed, but quickly defining the user stories will get everyone working on relevant tasks sooner.

Allows room for interpretation, creativity, and conversation

Nobody wants to be given a list and told exactly what to work on or build. The best user stories help the team understand broad goals and context which then sparks discussion and collaboration. It is also useful in eliminating hidden assumptions team-mates might have about a task.

User stories allow you to say why the features you’re proposing to build makes sense. A user story answers 3 important questions:

- Who are you building this for?

- What are you building?

- Why are you building this?

Answering these questions will tell your team the specific circumstances to build by so that they can work appropriately. For example, take a look at how the context of a user story is greatly affected by one of the three components:

As a user, I want to filter items by item type so that I can see how my team’s time is being used between features and bugs on a weekly basis.

As a user, I want to filter items by item type so that I can create a report on everything we did this month for my boss.

Notice how changing one component of a user story would change your approach entirely? In the first case, you would probably display this information in a chart or graph for a simple breakdown of your team’s time. In the second example, you would likely create a function to export the data so it can be shared and presented.

With user stories, everyone in your team knows exactly “who,” “what,” and “why” they are building features. Each component adds a necessary layer of context to give your team a proper start. A user story immediately directs the focus to a specific circumstance which provokes further discussion and careful revision. The end result is that your team becomes more focused on delivering solutions to user problems as opposed to merely delivering functional code.

How to write user stories

Now that we’ve listed some reasons why you should write user stories, here’s how to actually write them.

I.N.V.E.S.T.

The I.N.V.E.S.T. guideline to writing user stories is almost universally accepted as the standard to work by. The acronym was made popular by Bill Wake’s original article from 2003. Our interpretation:

(I)ndepdendent: You should be able to prioritize and rearrange user stories in any way with no overlap or confusion.

(N)egotiable: As previously discussed, a good user story can be reworked or modified to best suit the business. User stories are not an explicit set of tasks.

(V)aluable: User stories need to be valuable. By this, we mean valuable for the business or the customer. If it’s not, why would you have your team work on it?

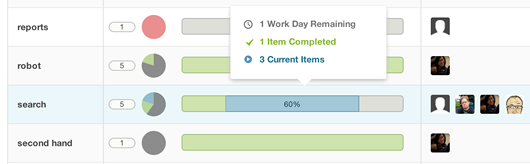

(E)stimable: A good user story can be estimated. It’s also important to differentiate time estimations from an exact timeframe. A rough estimate is beneficial to allow teams to rank and schedule their priorities. At Sprintly, we allow users to categorize their stories and sub-items into sizes (small/medium/large/extra large) so that they can better prioritize their stories.

(S)mall: We definitely recommend keeping your user stories small. While we don’t suggest an exact timeframe to stay in, writing user stories that focus on smaller tasks allows for greater focus. The larger a story is, the harder it is to estimate and easier it is to get caught up in sub items that should have probably been their own stories.

(T)estable: Before a user story is written, it is essential that a criteria to test it is in place. Outlining the testability first ensures that the story actually accomplishes the goal you are trying to achieve. A story is not finished until it is tested. For maximum productivity and team alignment, make sure your team knows how their work will be tested.

We tend to view testability as the fourth major component of a user story. Having your team know your stories’ testing parameters beforehand plays a big role in how they decide to take it on.

Sub-items

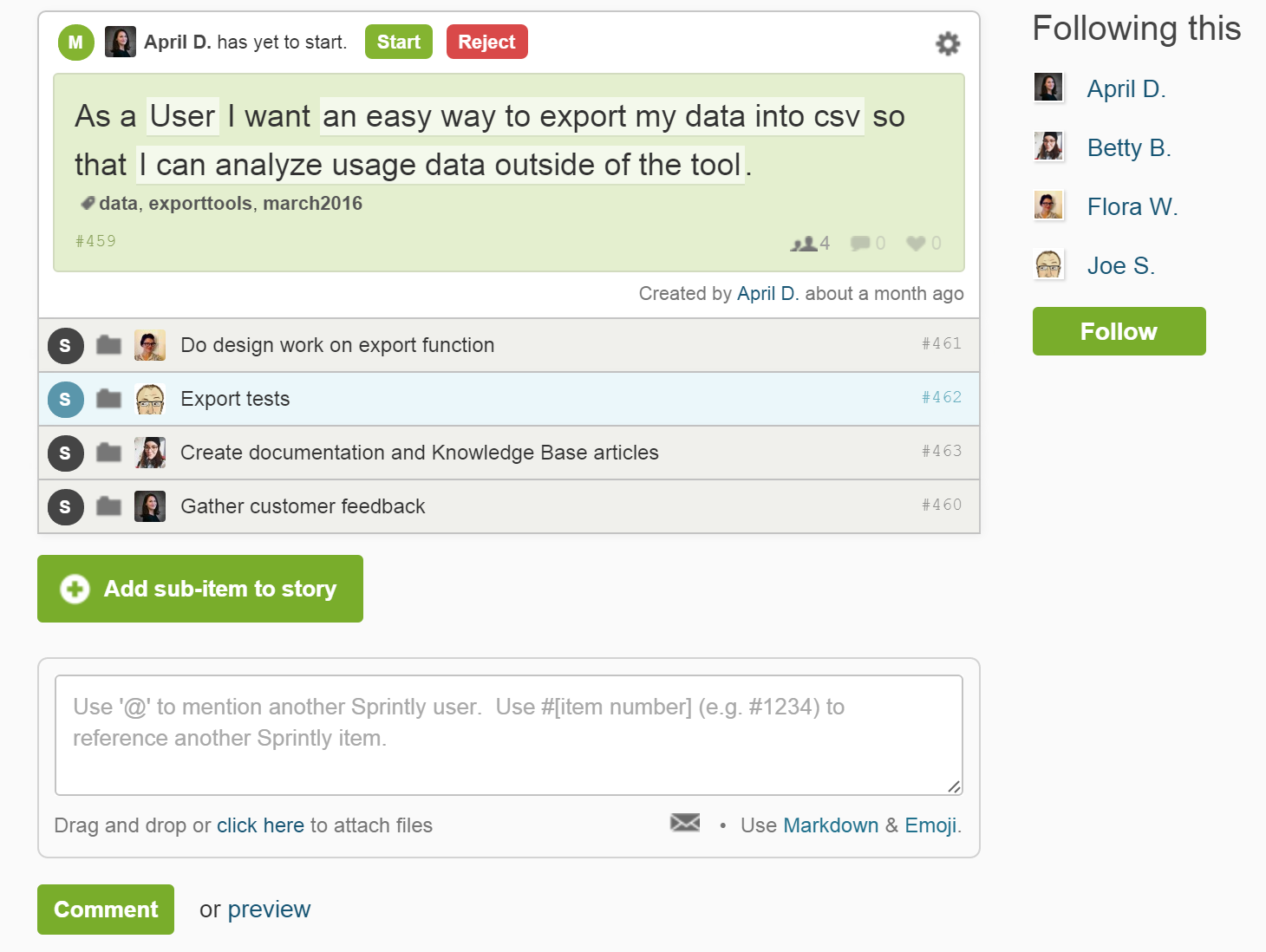

With I.N.V.E.S.T. in mind, you can now start thinking about writing user stories. At Sprintly we consider any project that contains sub-components a good candidate for a user story. Sub-items are tasks or tests you can list under your user story to provide a clearer vision of what needs to be done before the user story is complete.

Once again, it’s important to remember that everything about a user story, including its sub-items, can be reworked to best fit the needs of your business. Sub-items are great for providing additional direction and details for what needs to be done. Take this user story for example:

Sprintly supports collaboration on both the main user story and its sub-items, allowing team members to comment, tag other team members, make edits, and more. The more communication there is around stories and tasks, the better the outcome.

Things to avoid when writing user stories

While we think writing agile user stories isn’t difficult, there are still ways you can mess it up. Here are some common pitfalls you should avoid.

Increasing the scope of your stories

Knowing that it’s good to rework and modify your user stories, it’s easy to end up increasing the scope of your story and taking away from its effectiveness as an agile tool. Don’t be afraid to break a story into two if the scope becomes unworkable. On the other hand, reworking a story to decrease the scope should be a welcome time saver for your team.

Treating technical tasks like they are user stories

It’s easy for your team to get in the habit of framing everything as a user story. Sometimes teams might go so far as to take simple technical tasks and conceive those as stories. This is sometimes because they feel stories need to be broken down into smaller and smaller pieces. Other times it comes from the way a team tracks velocity and could be a symptom of your team not understanding the difference between tracking effort versus results. Going out of your way to label tasks as individual stories will just create confusion and waste everybody’s time.

Rewording the “want to” phrase as the “so that” phrase

“As a user, I want to be able to access my client list so that I can view my client list.”

Getting to the value part of the user story right is often tricky. Without proper analysis, you can easily end up with a story that describes what you are building, rephrased in 2 different ways, without answering the “why.” In the user story example above, it doesn’t describe why the user wants to view the client list. Making sure that there is an answer to the “Why?” is important.

Including multiple components in your user story

“As a user, I want to be able to access my client list so that I can save, share, and email the client list.”

You may be tempted to write comprehensive user stories that include either multiple “want” components, “so that” components, or both. It’s important to remember: if you can divide a user story into multiple ones, you should do it. Don’t worry about filling or “wasting” space on a board with your stories. If your team can understand what needs to be done, you are doing the right thing.

User stories are a great tool to aid your software development process. They are easy to work with and relatively simple to master. We hope our overview on user stories will help you and your team get started.

—

Interested in trying out User Stories in Sprintly? Sprintly requires no configuration or training and your team can be up and running in seconds. Click here for a free 30 day trial (no credit card required).