As a teenager, I remember playing strategy games like X-COM, Civilization, and Red Alert.

These games use a mechanic known as “the fog of war.” When a player starts the game, they are immersed in an overhead map that is shrouded by darkness. The only way to reveal your surroundings is to explore. As you make moves, more and more of the map becomes visible.

This puts the player at a strategic disadvantage: they can’t see nearby dangers, obstacles or opportunities. Each successful move requires a bit of luck.

Does this scenario sound familiar?

The “fog of war” provides a perfect metaphor for how developers are asked to work. They’re plunked in projects where they’re asked to work on a specific piece of code, but they’re kept in the dark about everything surrounding that task.

For developers, seeing “the whole game map” is important. Having a clear view of the entire scope helps them make good decisions. Here are some questions they might ask:

- Why are we building this feature? How does it improve the lives of our customers?

- What is the history of the code surrounding this feature?

- What other parts of our application does this feature affect?

- What other parts of our business does this affect?

- How will we measure the success (or failure) of this project?

Once they can see the entire topography, developers can start working with purpose. They’re no longer cogs in a machine but deliberate actors who can influence the success of the project.

There are also huge motivational benefits. Joe Stump summarizes:

Developers are often kept in the dark about the problems behind the task. This means some of the most creative thinkers in a business are not thinking critically about the issues around a given objective.

For instance, if I’m the backend developer and you tell me to implement some API endpoint, I’m 2-3 steps removed from why you’re needing that endpoint.

But if I’m responsible, alongside you, for moving conversion up 20%, I’d be immersed in the thinking around that problem because my work as a developer is more concretely tied to business success.

This highlights the importance of identifying the vision and mission behind each project:

- Vision: Why are we doing this? How does this change the world?

- Mission: What’s the objective? Where do we need to end up?

When they understand the vision and mission, developers also become valuable partners during the planning process. They can foresee potential landmines in your path and help you avoid costly mistakes. In this Smashing Magazine article, Paul Boag describes the dangers of not including a developer in these meetings:

Back in the heyday of Digg, I remember a conversation between Daniel Burka (Digg’s lead designer) and Joe Stump (its lead developer). They told a story of a design change to the Digg button that Daniel wanted to introduce. From Daniel’s perspective, the change was minor. But upon speaking with Joe, he discovered that this minor design change would have a huge impact on website performance, forcing Digg to upgrade its processing power and server architecture.

What you can do

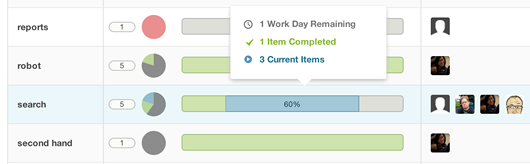

Here at Sprintly we do our quarterly planning meeting with representatives from product, support and engineering.

After the meeting’s done, we create a document with a list of spec’d Sprintly stories we’ve decided to work on for the next 3 months. This is sent off to the whole dev team who get to sign-off before work begins.

Managers aren’t generals, developers aren’t soldiers

Sometimes managers act like each project is a clandestine operation, and that information should only be given on a “need to know basis.” This Wikipedia piece articulates why this might happen:

Need-to-know (like other security measures) can be misused by persons who wish to refuse others access to information they hold in an attempt to increase their personal power or prevent unwelcome review of their work.

This kind of protectionism doesn’t result in better code, projects or increased sales. Don’t keep developers in the dark. Invite them to become invested in your overall strategy.

Note: Justin Abrahms wrote an excellent companion piece to this, called The Omission of Why.

Also, if you’re looking for a good framework for keeping product teams accountable, check out Jason Evanish’s product thesis post.